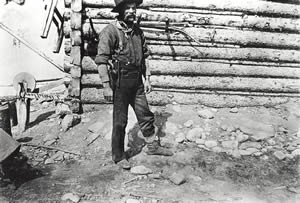

Jack Dalton was either a “dapper, well-dressed ladies man” or a “scoundrel” depending on who you asked.

Jack Dalton was either a “dapper, well-dressed ladies man” or a “scoundrel” depending on who you asked.The Chilkat Tlingits controlled the three main trade routes to the interior over the Chilkat, Chilkoot and White Passes, thus monopolizing trade with the Athabascan Indians. The name “grease trail” was given to these routes, as the most important trade item carried over waseulachon oil extracted from the tiny candlefish that still run area waters each May.

Chilkat Tlingits at potlatch hosted in Klukwan in 1900.

The Ganaxtedih Ravens and the Deklawedih Eagles of Klukwan owned the route over the Chilkat Pass and the Tluknahadi Ravens of Chilkoot and Yendustucky owned the trails over the Chilkoot and White Passes. Other clans were allowed to participate in the trading, but the chiefs of the owning clans organized the trips and conducted the formal trading operations. Each Tlingit chief had an Athabascan trading partner with whom he dealt exclusively. Traditionally, Tlingits returned with furs, hides and copper nuggets traded from the Athabascans. Trading parties, lasting a month or more, often consisted of as many as 100 men, each of whom would carry 100 plus pound loads. Upon the arrival of white traders, the Chilkats acting as middlemen between the traders and Athabascans became quite wealthy.

This trade monopoly was not broken until 1890 when E. J. Glave, John (Jack) Dalton and several others were hired by Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper of New York to “explore the Interior of Alaska and discover the headwaters and tributaries of the Yukon, Copper, Alsek and Chilkat Rivers.

“The Tlingits managed perfectly astonishing loads of 100 pounds and more on steep mountain trails and across broad snow fields… In winter almost the whole trip is done on snowshoes, which are especially large to prevent the packer, who carries, in addition to his load, a gun and axe, from sinking into the snow under his weight. Sleds were seldom used and the numerous wolflike dogs were nowhere pressed into service as draft animals.” Aurel Krause, Die Tlinkit-Indianer, 1885 (translated 1956 by Erna Gunther).

“…Dalton and I decided to stay to see the last of the caravan and pick up any odds and ends that might be left behind; we found plenty of this material with which we brought up the rear of the procession, loaded with a curious assortment of property. Dalton carried three pairs of snowshoes, one gold pan, one bread pan, four saucepans, (all about the same size, strung around his waist on a belt), besides which he had a rifle, revolver, ammunition, etc. I was loaded with one bucket, one big kettle, teapot, blankets, sack of books, camera, overcoat and a wild duck. We had pots and pans, whose musical melodies might have aptly served as the heralding strains of the Salvation Army; but the climax of our eccentric march was reached when Dalton packed me and my load on his back across a stream. How glad I was that no camera fiend was nigh to have taken that perambulatory mass of grotesquely, smothered humanity!” Interior Alaska in The Alaskan 13 Sept. 1890.)

Jack Dalton “the scoundrel,” who took over the Chilkat Pass trading route from the Tlingits and kept a shotgun loaded with rocksalt under the bar of his saloon to deal with unruly patrons.

Dalton and Glave, seeing the potential of a trade route, returned in the spring of 1891 to check the feasibility of taking packhorses over the Tlingit trails. “Fearing that we might have a lot of soft snow to cross on the summit, we constructed sets of four snow-shoes for our horses… The horse’s hoof was placed in a pad in the center of the shoe, and a series of loops drawn up and laced round the fetlock kept it in place. When first experimenting with these, a horse would snort and tremble upon lifting his feet. Then he would make the most vigorous efforts to shake them off. Standing on his hind legs, he would savagely paw the air, then quickly tumble onto his forelegs and kick frantically. We gave them daily instruction in this novel accomplishment till each horse was an expert….” E. J. Glave. Pioneer Packhorses in Alaska in Century Magazine Sept. 189

Pyramid Harbor in 1885. This small settlement located across the mouth of the Chilkat River opposite present day Haines, grew up around a cannery and as quickly vanished when the cannery closed. The “harbor” has since filled in with silt.

This journey was important to Alaska history in that “It proves a possible transport where none before existed… The inaccessibility of the interior of Alaska has barred the miner and the prospector; but now the road is open.”Alaskan Sunlight and Shadows in The Alaskan 21 Nov. 1891.) Glave died a few years after this trip, but Dalton remained in Chilkat country. He developed trading posts and a toll road into the interior along the Chilkat “grease trail.”

Dalton Cache restored in the 1990s. This building can be seen at U.S. Customs at about 40 mile on the Haines Highway.

Dalton Cache restored in the 1990s. This building can be seen at U.S. Customs at about 40 mile on the Haines Highway.At this time, Pyramid Harbor (west, across the Chilkat River from Haines) was the deep-water port for this region and the beginning of Dalton’s trail. By 1896, Dalton had established trading posts at Dalton cache (the building can still be seen at U.S. Customs 40 Mi. up the Haines Highway), Dalton Post (just off the highway at 106 mi. in the Yukon) and Champagne (on the Alaska Highway). Miners, prospectors, cattle drives and even a reindeer drive followed this trail to the interior. Approximately 300 miles long, the Dalton Trail led from Pyramid Harbor to Ft. Selkirk on the Yukon River. From Ft. Selkirk, log rafts floated men, horses and cattle to Dawson City. Dalton hired out to guide groups over his trail and in 1898, he established a short-lived pony express to carry mail and people between the Yukon and Pyramid Harbor.

Many fortune-seekers walked the Dalton Trail including the “Mysterious Thirty – Six.” On March 9, 1898, 36 men arrived at Pyramid Harbor aboard the SS Farralon. Sworn to secrecy as to their destination and intentions, these men created quite a stir of speculation. Unofficially it was learned that ex-Lt. Adair of the U.S. Calvary represented the Standard Oil Company as he led these men, gathered from all over the country, in search of gold. They traveled up the Dalton Trail as far as Champagne and established Pennock’s Post. Finally, in April 1898, they arrived back at Shorty Creek where they staked and worked some 40 claims. Like most gold seekers from the days of ‘98, they returned with many memories and little gold.

By 1899, Dalton received official permission from the U.S. Government to charge a toll for the use of his trail. “The trail did not become a toll-road until the spring of 1899, then by license of the United States Government, tolls were authorized on March 9th and April 10th to be levied as follows:

| Cattle, horses, mules, burros | $2.50 |

|---|---|

| Goats, Sheep, Swine | 50¢ |

| Single horse with sled or wagon, unloaded | $2.50 |

| Two horses with sled or wagon, unloaded | $5 |

| Four horses with sled or wagon, unloaded | $10 |

| Dog team, two dogs | $1.50 each (25¢ each additional dog) |

| Merchandise of all kinds | 1¢ per pound |

| Foot passengers with pack of more than 25 pounds | $1 |

| Natives of Alaska with pack of 25 pounds or less | free |

No tolls, of course, could be collected under this license in Canadian Territory.” Martin, Archer. Porcupine-Chilkat Districts. Report under the Porcupine District Commission Act 1900. Victoria, B.C. 1901.

The discovery of gold at Porcupine Creek, 36 miles up the highway from Haines, and of course the Klondike Gold Rush in 1898 caused brief flurries of use along the trail. By 1900, the White Pass and Yukon Railroad and the construction of new trails from Porcupine to Haines by miners wishing to avoid the toll, caused a decline in the use of the Dalton Trail. After a many thousand dollar and several year investment, Jack Dalton moved on to other projects. In the 1920s a road was cut to the Canadian Border along the east side of the Chilkat River. The Haines Cutoff Highway, built in the 1940s, follows the general route of the Dalton Trail. Today, the old Tlingit “grease trail” provides an important road link to the interior of Alaska and the Yukon.

Cynthia Jones, 1988

Updated by Blythe Carter, 2013